Who is really getting cancelled?

This last weekend The Age published an in-depth three-part series on so-called cancel culture. I was interviewed for the second part, which focused on a philosophy professor here at the University of Melbourne, Holly Lawford Smith. In February, Lawford-Smith created a website aimed at collecting anonymous, unverifiable anecdotes about trans women, with the goal of using them as fuel in her crusade against essential civil protections like bathroom access. At the time, I signed an open letter protesting the website and wrote a blog post about the issue, which I assume is how The Age heard about me.1

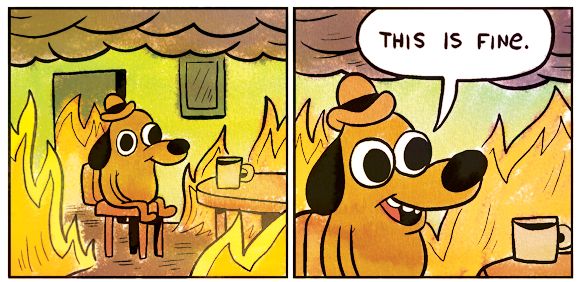

The series in The Age, and my role in it, has left me exhausted and despairing. It has confirmed to me just how persistently and deeply transgender people are misunderstood, even by well-meaning people operating in good faith. It’s so easy for folks to be misled by their own priors in combination with the framing provided by an enormous propaganda machine dedicated to spreading misinformation about who we are and what we want.

I despair because I don’t know what to do or how to fight it. I’m exhausted because I’m already so tired of trying.

Since February, I’ve been asked multiple times, often by rather high-profile media outlets, to be interviewed about “cancel culture.” This is a topic in which trans people are used as props to take the role of “woke person who demands that other people never say anything offensive because it hurts their feelings.” Never mind that this is not actually what most of us are saying or asking for. Never mind that the only reason many of us agree to serve in this role is because the alternative is to remain silent and risk losing our fundamental human rights. For most people, the issue of “cancel culture” is an abstract intellectual battle. For us, we are in an actual real battle with actual real consequences to our actual real lives. It is a battle about whether other people can take away our right to appropriate medical treatment, our right to exist in public without reprisal, and our right not to lose our jobs for being ourselves. It is about whether we have the right to be ourselves without fear of losing everything.

Notably, I’ve never been asked for an interview about any of our actual real concerns. I’ve not been asked why we are so afraid that we’ll lose those rights (answer: it’s because a lot of people with power are trying to make it so we do; see below). I’ve not been asked if we think the precise technical definition of gender is meaningful or relevant (answer: most of us do not. As a cognitive scientist, I think it’s scientifically interesting and the philosophers have it all wrong; but the entire question is a distraction from the important issues). I’ve not been asked if we actually think that lesbians should be forced to date people with penises or straight women should be forced to date people without (answer: almost everyone would say no). I’ve not been asked what most trans people’s biggest actual concerns are (answer: almost always things like access to medical treatment without excessive gatekeeping, policies that ensure we can’t lose our job or kids for being trans, and laws that ensure our safety if we are outed in public places – not whether people accidentally use the wrong pronoun or say something inadvertently offensive).

I am asked for interviews about “cancel culture” and nothing else because, by and large, most media outlets don’t actually care at all about trans people. Their concern begins and ends with their ability to use us as a prop in a culture war that we didn’t even ask to take part in.

As a result of this, I usually say no to these interview requests. I don’t like doing them. I recognise that the framing of the topic inherently sets me up to be a stooge, to play a role that I fundamentally reject. My views are far more complicated than this role allows for. I think freedom of speech is important! So is academic freedom! I just don’t uncritically think that these things are the only things that matter.

The other reason I don’t do interviews is that I’m not an activist. I said when I came out that I didn’t want to be one, and that is still true. I want to be known for my scientific accomplishments, not because I’m The Trans Dude. I fear that I lose my professional credibility every time I say something about transgender issues. I have a career and a life and a family and so many things that are way more meaningful to me than going in front of hostile audiences to be misunderstood when I try to defend my right to be myself.

Given these factors, why did I take this interview? Well, basically, James Button seemed to me like the best possible case of a mainstream cisgender journalist. He struck me as professional, aboveboard, and intelligent. I thought he was genuinely acting in good faith and honestly wanted to understand where I was coming from. (I still think that.) I thought that if I couldn’t get someone like him to understand my points, what chance did I have with someone more hostile or ignorant?

You might ask why I should care about what other people think anyway. I care because other people are the ones with the power to take away my rights or the rights of vulnerable people in my community. You might also ask why I think it’s my role to do something about that. Well, I’m uneasily aware that as trans people go, I’m far more privileged than most (mostly because I spent most of my adult life in the closet, which itself doesn’t say great things about our society). I have a stable job with a fair amount of prestige, supportive friends and family, and a lot of cultural capital. If I can’t speak out for us, who can? Who will? I can’t look myself in the mirror if more vulnerable trans people than myself pay the price of my silence. I can’t view myself as a moral person if I hide in fear rather than doing what I can to stop the fount of trans-related misinformation spreading through our culture.

I thought the odds were good that the piece James Button wrote would be biased – with that kind of framing it couldn’t help but be – but at least if I talked to him, I’d be able to do what I could so that a glimmer of our real concerns came through. And I trusted in his integrity enough that he would at a minimum not intentionally distort what I said or try to make me look like a crazy nutcase with an irrational vendetta.

I’m pleased that my assessment of his character, at least in regards to his treatment of me, was correct. I liked him and I enjoyed our conversation. He showed me the paragraphs of the article that were about me in advance and gave me the opportunity to clarify things in that part if I thought he’d gotten something wrong. He warned me that for space reasons a lot of the nuance in our conversation probably wouldn’t make it into the article; I expected that. And indeed, I don’t think the article treats me (as a person) badly.

But I was nevertheless pretty dismayed at how the article in general read.2 There were errors, omissions and biased judgments throughout.3 As someone who often writes complex papers on thorny topics, I appreciate that it’s often nigh-impossible to eliminate all errors, and editorial judgment calls are inevitable because we are all human and all have our own ways of looking at the world. However, it’s notable that all of these biases were in the direction of making the trans “side” look less legitimate. The open letter in support of trans people was not linked, but the transphobic website was. Only about 10% of the article (550 words or so) contained my contribution, with another 375 words devoted to other people on my “side”.4 Only four people on my side were quoted in total and only two of us, myself and Professor Julie Willis, received more than a sentence or two of coverage. In contrast, most of the over 80% of the rest of the article was devoted to the other side, airing the perspectives of multiple individuals from Holly Lawford-Smith to Kathleen Stock (another gender critical philosopher embroiled in her own freedom of speech issue) to Helen Pluckrose (an activist who has made a career of criticising “wokeness”) and many more (Tim Lynch, Jane Clare Jones, Nicole Vincent, Cordelia Fine, Joo-Cheong Tham, etc).

That does not seem very balanced to me.

Even more problematically, the article pushes back on or asks rhetorical questions about nearly every claim from “my” side, while frequently unquestioningly regurgitating biased or inaccurate claims from the other. It casts the French code in opposition to us, noting that it “stresses that universities must not try to protect staff and students from feeling offended or shocked or insulted by the lawful speech of another” – without noting that our primary problem was not that we were offended or insulted, but that Lawford-Smith’s website and her uncritical spread of misinformation about us had the potential to do us actual harm.5 It quotes Cordelia Fine as saying that the open letter caused “considerable harm to Holly’s reputation by making serious, unsubstantiated claims about her conduct” without pushing back on that incorrect characterisation or noting that Holly’s claims about us are even more serious and unsubstantiated, and the possible harm to us is not just reputational but goes far beyond that. It quotes Professor Tim Lynch as saying that he thought the woke had created an atmosphere on campus where the non-woke were “keeping quiet for strategic reasons”, without noting that many transgender and minority staff already must keep quiet for strategic reasons and have been doing so for decades.

Astoundingly, it further quotes Lynch as denouncing the open letter by saying “our role as academics is to create a climate in which disagreement is not lethal” without noting that the only ones who have been actually killed by “disagreement” on transgender issues have been transgender people themselves.

It doesn’t stop there! The article quotes Jane Clare Jones as saying that “Humans are sexed. We are animal. We are embodied. Denying that is delusional” without noting that trans people do not deny this (and thus implicitly accepting her premise that we are delusional). What we deny is that biological features like chromosomes or genitalia should determine our social roles or rights; that is a very different thing. The article quotes Lawford-Smith as saying (completely incorrectly) that “woke ideology specifies that you’re not supposed to believe in or care about biological sex anymore” and “substantiates” this point by quoting a random trans woman on a television show who is talking about who she is attracted to and making no claim about what anybody else should do.

The article casts shade on the legitimacy of trans identities by noting that many trans people do not medically transition. Putting aside the fact that identity and medical transition are conceptually distinct, this ignores the fact that medical transition is increasingly difficult to access: people without many thousands of dollars and the cultural capital and free time to navigate the Kafkaesque gatekeeping processes in most countries simply cannot medically transition no matter how much they want to. Why is there so much gatekeeping, you might ask? It’s because of people like the gender critical feminists and their right-wing backers. They have created and spread these narratives that say we are delusional and unable to make these decisions for ourselves, or that offering hormone blockers is child abuse (despite the fact that it is a recognised evidence-based intervention for both cis and trans people), or that these procedures are cosmetic and optional rather than fundamentally important for our health.

I could go on, but let me instead take a step back and note some of the wider context here, which any trans person who read this article would have been acutely aware of. The series in The Age overlapped with the Transgender Day of Remembrance, a day devoted to remembering the trans people who have been killed for being trans. There were a record number this year. I don’t know if the timing was deliberate or accidental, but it is hard to read it as anything other than tone-deaf at best, deliberately antagonistic at worst. It was also a part of a constant wash of unfavorable media coverage that uncritically regurgitates the same lies and misinformation. In just the month before it came out alone, the BBC ran an article called “We’re being pressured into sex by some trans women” which extensively quoted a cis woman who was herself a rapist and later wrote a blog post calling for the lynching of trans women. Netflix ran an transphobic hour-long special with Dave Chappelle; when trans employees protested, they were fired. In the meantime, 2021 saw a record amount of anti-trans legislation in the US, along with increasing anti-trans propaganda in the UK, mostly fuelled by misinformation.

It is frankly absurd that this is the world we live in while countless articles suggest that the main issue is that we are too sensitive.

Reading the article was therefore distressing to me. But perhaps the most distressing part of it is that I stand by my estimation of James Button’s character. I genuinely do think he was trying to write a balanced piece. And this is the crux of the issue: if this is the result when somebody of good will actually does their best, what hope do we really have?

I mean, maybe I’m wrong about his character or his intent, but I don’t think so. I think he wrote what he did for a few important reasons. First, he came in with strong prior beliefs that held freedom of speech as one of the most important ideals. He admitted as much to me, and I think most journalists probably have such beliefs – it is one of the basic tenets of the profession after all. I have a lot of sympathy with this; as I said to him, I used to believe it myself 20 years ago.6 The end result of any strong cognitive bias, though, is it is very hard to avoid interpreting points made against your view in the most uncharitable manner, and points made in favour of your view in the most charitable way.7 Second, it was probably hard for him to find people to speak up in support of the letter. This is because most of the people who signed it are precarious in some way, with a lot to lose: junior people in fixed positions, trans people who know they will get harassed, and so forth. When somebody is actually being silenced you don’t hear from them, and that’s what’s going on here: many folks are actually afraid of getting attacked or losing their jobs or not getting hired again. And finally, there is so much misinformation out there that it is difficult for a cisgender person to be aware of it all. It is a deliberate Gish Gallop strategy, which we also see for other kinds of misinformation like around vaccines or climate change: put so much crap out there that the other side gets overwhelmed and cannot possibly refute everything.

As an example, writing this stupid blog post has taken me many hours. I refuted a bunch of misinformation here but there is still so much that I haven’t, because I simply don’t have the time. This is not my actual job and it has taken more time from my real responsibilities than I’m happy with. I have so much else to do. But again, if I don’t write this, who will?

Honestly, I want nothing more than to not have to be constantly afraid of what rights I or my community might lose if I stay silent. I want to never get another interview request on this ridiculous topic with this ridiculous framing. I want to stop having to think about how to balance my own safety and mental health with the needs of my community.

The question I keep going back to is this: what benefit was there from me giving that interview? As far as I can tell, there was very little. Maybe it was even a detriment. Maybe by being there I implicitly validated the “cancel culture” framing as legitimate. Maybe my presence made it look to a superficial observer like it was a “balanced” article even though it wasn’t.

I do know that the interview was costly for me. I enjoyed the conversation with James, but all told this whole endeavour took many hours – a pretty big sacrifice given my intense job and small children. It definitely was costly emotionally, not just in doing the interview and recovering from it, but in handling the distress when the article came out.

Was it worth it? Maybe it was a better article for having me in it? Maybe my words reached someone who they otherwise wouldn’t have?

Maybe? I don’t know. All I know is that the costs are really obvious and the benefits are not.

This is what happens when you are part of a very small and hard to understand minority. There simply aren’t enough of you to withstand a foe who is far more numerous and far better funded, a foe who is unconstrained by facts and happy to use you as a scapegoat for their own larger ends.

How long can I, even with all my privileges, last? At what point will I say “I can’t do this anymore” and stop speaking out, stop trying to explain to people the nuance and the truth of my life? When will I decide that life is too short to spend it saying the same things over and over to people who are exposed to so much misinformation – and whose prior beliefs are so strong – that they can’t hear what I’m actually saying?

And yet I can’t bear to give up. Not yet. If I do give up, I won’t be able to face myself if (or when) transgender rights are further curtailed: kids given conversion therapy, medical treatments restricted and doctors thrown into prison for trying to provide gender-affirming care, people prevented from going into using public bathrooms safely. Unlike the inchoate and misplaced fears of gender critical feminists – who blame trans people for problems that are either nonexistent or largely caused by men and the patriarchy – these are real things that are already happening and being enshrined into law. Maybe not (yet) in Australia, but where the UK and the US go, Australia usually goes too, and people like Holly Lawford-Smith provide the institutional and academic credibility for these movements.

So my thoughts go, back and forth, back and forth. If every trans person stays silent, we will lose our rights and the small scrap of social progress that others have bought dearly. But speaking out is costly: very costly, far more costly for trans people than for others. All others need to do is outlast us. And they can, because there are so many more of them and they have so much more of the power.

You want to talk about cancel culture? Ask yourself who is really being cancelled. It’s not the people being given huge media platforms to talk endlessly about how they are being silenced. It’s the people who are actually silenced, the people you don’t hear. It’s the people who are scared to talk – the people who journalists can’t even find to interview because they legitimately fear for their livelihood or safety if they speak out. It’s the people who are murdered in such numbers that there is an entire day of the year dedicated to our deaths. It’s the people whose words are misunderstood or ignored or distorted any time they do manage to talk. It’s the people who aren’t trying to restrict the rights of others, but are only trying to preserve their own.

Please, folks. Stop believing and spreading lies about us. Listen to transgender people and what we are really saying and what we really want. Not what other people tell you we’re saying, not what the caricatures and biases in your mind say we’re saying, but what we are actually saying and what we actually fear and what we actually want.

Stop cancelling us.

-

I really, really don’t want to go into the particulars of this case; read my post if you care. Instead, I want to talk in more general terms about this latest episode and the reason for my despair. ↩︎

-

I’m going to concentrate on Part 2 because it is the part where I appeared, and I don’t have the time or energy – or, frankly, emotional reserve – to go through the whole thing. ↩︎

-

Here is a good overview of a lot of them, above and beyond my points here. ↩︎

-

This consisted of several paragraphs from an interview with Professor Julie Willis, chair of the university’s diversity and inclusion sub-committee, a sentence quoting NTEU branch president Annette Herrara, and two sentences quoting the trans convenor of the union’s Queer Unionist group, speaking in a personal capacity. ↩︎

-

Again, have a look at my blog post on the topic to see what I actually have to say. ↩︎

-

I still think freedom of speech is very important, particularly speech of those with less power. What has changed for me is that I have studied cognitive science and misinformation, and I have seen over and over that platforms where all speech is allowed regardless of truth value or legitimacy invariably results in untrammeled spread of misinformation and conspiracy theories. False news has an enormous advantage over true news for lots of good reasons (for one thing, it is not constrained by the truth, and thus can evolve to perfectly fit with the cognitive biases that make it easier to learn and more exciting to pass on). Malign influences from foreign entities to domestic terrorists have used this to push agendas that have undermined free and fair elections, effective vaccination responses to COVID, support for action against climate change – and, yes, movements like BLM or transgender rights. As a society, I think we must take the threats imposed by misinformation seriously, and people are making a huge mistake if in their desire to feel like righteous warriors for freedom they fail to engage honestly with this. ↩︎

-

I saw this myself in the first set of proofs James showed me. Despite taking pains to emphasise in our interview that my main concern with Lawford-Smith’s website was that it make it possible to create potentially false “evidence” that would then be used to support the removal of transgender freedoms, his first draft focused on the (much more minor) point that cis people always think we’re making, which is that her views are offensive to trans people. It speaks well of his integrity that he did show me these things and that he graciously changed them when I pointed them out, so this is not in any way a dig at him. It is an illustration of how ingrained and invisible biases can be to those who have them. ↩︎